24 Jan, 2026

3 min read

Nostalgia for Early 2000s Economic Boom Sparks Social Media Trend Among Young Chinese

Amidst a difficult job market and limited economic prospects, young Chinese are increasingly engaging with nostalgic content centered on the country’s early 2000s economic boom era. This trend has gained significant traction on social media platforms, serving as a discreet outlet to voice dissatisfaction with current economic challenges without provoking censorship.

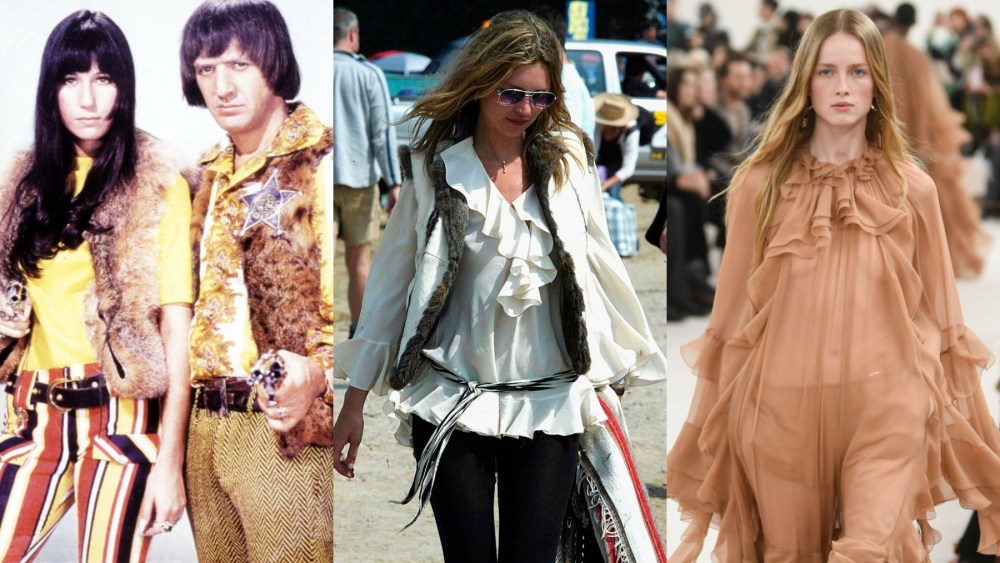

Over the summer, the hashtag "beauty in the time of economic upswings" surged in popularity, accompanied by images and videos showcasing celebrities, fashion, and advertising from two decades ago. This spike coincided with the graduation of 12.2 million university students, entering one of China’s toughest employment landscapes in recent memory.

Although China’s economy is expected to grow around 5% this year, analysts characterize it as a "dual-speed" economy—manufacturing and exports remain robust while household incomes and consumption slow down considerably. This growth rate is roughly half that seen during the 2001-2010 boom period.

Social media users reflect this divide: millennial women often reminisce about greater career and consumption opportunities in their youth, while today’s younger generation confronts starkly limited options. Yaling Jiang, founder of ApertureChina consultancy, noted that the trend likely echoes widespread concerns over the diminishing value of higher education and intensifying competition in the job market.

The growing popularity of this nostalgic content also poses a subtle challenge for Chinese authorities, says Xiao Qiang, founder of China Digital Times. "By using familiar symbols like fashion and makeup," he explained, "the trend conveys economic frustrations and pressures indirectly, fostering shared nostalgia and subdued criticism without overt political statements."

This ambivalence complicates censorship efforts, as most posts celebrate the aesthetics and optimism of a bygone era rather than explicitly criticizing current conditions.

Capitalizing on this surge of interest, luxury and consumer brands have aligned marketing campaigns with the boom-era theme. Giorgio Armani, Tom Ford, Valentino, and others have sponsored posts on platforms like RedNote, China’s Instagram equivalent, while numerous retailers on Alibaba’s Taobao promote early-2000s-inspired merchandise. Beauty products and footwear are also framed as "millennial classics reborn," enhancing brand visibility through the wave of nostalgia.

However, fashion analysts observe that these vintage styles are not widely adopted on the streets. Yaling Jiang explained that marketers primarily use the trend for branding rather than to revive the exact looks of the early 2000s.

Makeup trends today contrast sharply with the brighter, futuristic styles of that decade. Present-day aesthetics favor subdued, “glass skin” looks featuring moisturized, monochromatic palettes—reflective of the more cautious economic climate—unlike the bold metallic tones and dramatic color contrasts of the boom years.

As one beauty blogger succinctly put it, "During periods of economic growth, makeup aims to look luxurious and exude the confidence that comes with career ascendancy and optimism."

This social media phenomenon illustrates a complex interplay between nostalgia, economic reality, and expression under tightly controlled media conditions in China, offering both a marketing opportunity and a subtle barometer of public sentiment.

Recommended For You

Israel Seeks to Strengthen Economic and Innovation Ties with Cebu

Jan 24, 2026

Isabella Garcia

Monopoly in Camotes Ferry Services Drives Up Costs for Residents

Jan 24, 2026

Rafael Villanueva

Viral Video Shows Ferris Wheel Spinning Wildly Amid Typhoon Uwan in Tagaytay

Jan 24, 2026

Rafael Villanueva

3rd Infantry Division Sustains Humanitarian Aid in Cebu Following Typhoon Tino

Jan 24, 2026

Carlos David